Noisy, ugly and dirty. Advertising has polluted cities, annoyed consumers, and jeopardised its own existence. Beyond a mass-media cacophony, brand communications’ significant carbon footprint and runaway consumption are certainly contributing to what economists call market failure.

In the UK, for instance, advertising produces 2 million tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions a year. That’s equivalent to heating 364,000 UK homes for a year, according to CarbonTrack.

In this sense, should messages such as a City of Melbourne campaign inviting people to cycle more even be allowed? On the one hand, it is better to communicate a solution (cycling) to the issue than not. On the other, if the communication contributes to the problem more than the solution, what’s the point of it?

Jerry Seinfeld’s 2014 infamous line at the Clio awards called out the advertising sector to its face: “I think spending your life trying to dupe innocent people out of hard-won earnings to buy useless, low-quality, misrepresented items and services is an excellent use of your energy.”

Still, contrary to that sentiment, marketers and their brands can (and should) move away from being part of the problem to becoming part of the solution for sustainable development and the industry’s own sustainability.

Offering a new outlook

The urbanisation megatrend wholly underpins other forces shaping the way we live, now and in the future. Although cities occupy only 2% of Earth’s landmass, that is where 75% of energy consumption occurs. Advertising growth is also concentrated in big cities.

Because of increased demand for ever more comfortable lifestyles, urban infrastructures have been feeling “growing pains” for decades now. Whether it’s energy, education, health, waste management or safety, cities’ services are struggling to keep up with their larger and “hungrier” populations.

The strategic opportunity here is to reframe brand communications from the promotion of conspicuous consumption to becoming a regenerative force in the economy of cities. That means using brands’ touch points as more than mere messengers, but rather delivering public utility services. I’ve coined it Urban Brand-Utility.

For example, Domino’s Pizza’s Paving for Pizza program fixes potholes, cracks and bumps said to be responsible for “irreversible damage” to pizzas during the drive home.

This may sound silly, but the US National Surface Transportation Policy and Revenue Study Commission estimates that simply to maintain the nation’s highways, roads and bridges requires investment by all levels of government of US$185 billion a year for the next 50 years. Today, the US invests about US$68 billion a year.

According to Bill Scherer, mayor of Bartonville, Texas: “This unique, innovative partnership allowed the town of Bartonville to accomplish more potholes repairs.” Eric Norenberg, city manager of Milford, Delaware, said: “We appreciated the extra Paving for Pizza funds to stretch our street repair budget as we addressed more potholes than usual.”

In Moscow, major Russian real estate developers approached Sberbank to collaborate on better infrastructure planning in residential areas. People’s opinions on local needs fuelled targeted campaigns, promoting loans for small businesses. The “Neighbourhoods” campaign generated nine times as many small-business responses as traditional bank loan advertising.

In other words, people had their needs met. And neighbourhoods become more attractive as a result. The city increases tax collection from the new businesses being set up, which also reduces the costs of having to deal with derelict areas.

A shift to serving citizen-consumers

If we could see ourselves as citizen-consumers, as opposed to individual shoppers in the market, every dollar spent would enable business to tackle the issues that matter most.

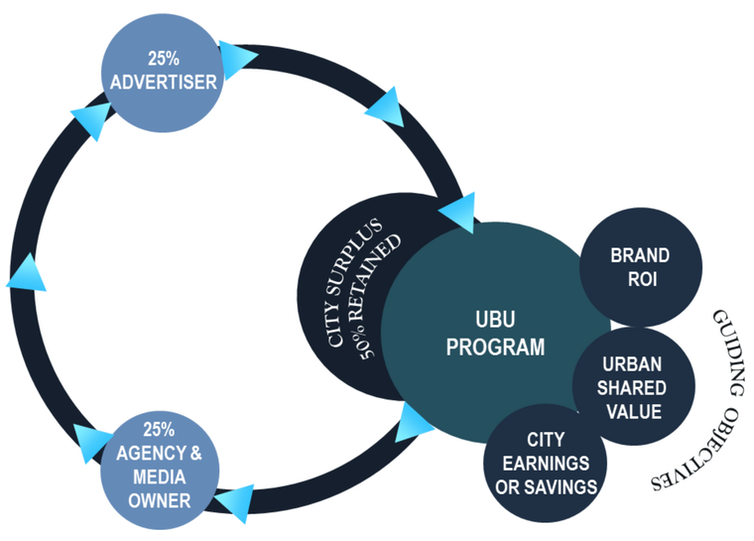

Here’s a hypothetical situation. Let’s assume Domino’s Paving for Pizza program is taken to its full potential, generating a large surplus to the City of Bartonville by minimising the costs of repairing potholes. Rather than treating this as a one-off campaign, smart mayors would try to create a virtuous cycle, where the city retains 50% of the surplus, 25% is returned to the advertiser, and 25% goes to the agency and media owner – a value only unlocked by repeating the approach.

This way, marketing budgets are effectively turned into investment funds. The returns are in the form of brand cut-through, happier customers, social impact and more effective city management, as shown in the model below.

In a circular economy, products and services go beyond an end user’s finite life cycle. Similarly, Urban Brand-Utility looks at brand communications as closed loops by designing a system bigger than fixed campaign periods, target audiences and business-as-usual KPIs.

Brands with some level of foresight will be able to broaden their audiences from customers to citizens and their revenue model from sales to the creation of shared value. These will be game-changers for profit and prosperity.

Markets, choice and competition are not just a consumer’s best friend, but their civic representation. After all, as one of the tribunes asks the crowd in Shakespeare’s Coriolanus: “What is the city but the people?”

Author: Sergio Brodsky, Sessional Lecturer, Marketing, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.