With more and more consumers increasingly resorting to digital and convenience-focused shopping, retailers and property owners are looking to innovate beyond their four walls to attract consumers.

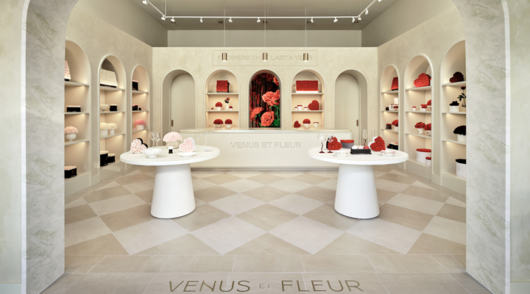

Some brands that want to differentiate themselves in order to attract customers have turned to museums or have browsed through magazines for inspiration to create spaces where the virtual and physical worlds collide, while some just want to create experience-focused retailing.

This new wave of thinking has given rise to a number of retailers experimenting with concept stores.

What exactly is a concept store?

Danny Lee, senior research manager at CBRE Australia, defined it as a store that delivers a new experience to consumers and said place-making is important to attract consumers.

“With real spending per person not growing over the past decade and with more competition and the threat of online retailing growing, retailers and property owners are trying to differentiate themselves to attract consumers,” Lee told Inside Retail.

Demand for experiential shopping, particularly from younger demographics, according to Lee, are driving retailers and property owners to step up with new concepts.

This is seen across all retail categories. For example, department and discount department stores are changing their store formats. Westfield has upgraded its food courts to resemble mini-cafes. There is a rise of F&B concept stores in the CBD, and experience centres like Samsung to draw consumers and increase dwell time.

“This trend will continue as consumers expect more shopping experience in the coming years,” Lee said.

With the rise of the idea of creating concept stores, there is also a surge in the trend of turning residential or some iconic buildings into unique destinations, like for instance the newly restored heritage-listed Rozelle Tramsheds, part of the Mirvac owned Harold Park in Sydney, opening as a food destination.

Lee said regardless of whether it is new or old, there is an increase in mixed use developments.

“Place making plays a key role to creating an attraction for the suburb,” he said. “State governments and policies are favouring transit oriented developments, which are mixed use developments around a transport node to achieve sustainable satellite towns.”

Lee said people still want to shop and make purchases in-store, according to their consumer and millennial surveys, but a shopper’s selection of a mall or a store would be based on its offering and shopping experience.

“New concepts and international brands are driving consumers into their centres,” he said.

Lee said technology and consumer expectations have always driven innovation and innovation is not new, it is always continuous. He said this could be good and bad at the same time. Good for consumers but bad for older model retailers.

The same changes in technology and consumer expectations have led to the decline in the presence of physical retailer establishments, with consumers reporting seeing fewer traditional “Main Street” business, according to an Ipsos Global Advisor study of 24 countries.

In Australia, the types of stores that are most markedly vanishing from local shopping areas are: bookstores, reportedly seen less often by 48 per cent of Australians compared to 39 per cent globally); news stands (41 per cent) and any type of independently-owned and operated (non-chain) stores (35 per cent).

In contrast, Australians are reporting seeing more or just as many drugstores and pharmacies (75 per cent saw more or just as many), eat-in restaurants (69 per cent), cafes (67 per cent, with a larger increase noticed in Australia than globally), and stores or restaurants selling readily-prepared or takeaway food (66 per cent).

Although the reported level of takeaway food restaurants is on the rise, only 11 per cent of Australians are eating takeaway food more often, compared to 18 per cent of people across the world. In fact, in Australia 35 per cent of people are buying takeaway food less often than three years ago (compared to 29 per cent globally).

An increase was also seen in the number of gyms/fitness clubs in Australia by 26 per cent of people, compared to 22 per cent globally. There are also more vacant stores, with 30 per cent of Australians seeing more of these (25 per cent globally).

According to the study, while consumers are shopping more in general than three years ago (both instore and online), a greater percentage of Australians are shopping more online (on average, 16 per cent are shopping more online across different products and services, and 12 per cent are shopping more in-store).

And the upwards trend in shopping online for certain products is having an impact on main streets: 38 per cent of Australians are buying books in-store less often, and 17 per cent are now buying books online more often than three years ago, leading to these stores being seen less often by nearly half of Australians.

Even more extreme is the change in banking habits, with 55 per cent of Australians banking in person less often and 46 per cent banking online more than three years ago. Relying more than ever on website and web-based advice, 36 per cent of Australians are making travel reservations in person less often and 26 per cent are making these online more often.

People still love to go shopping and going to stores, whether it’s a social occasion, or a day out with the family, but there is a crucial distinction between the act of shopping and where a purchase is made. The customer’s retail experience is an integral part of the consideration process, and more retailers are taking note.

Access exclusive analysis, locked news and reports with Inside Retail Weekly. Subscribe today and get our premium print publication delivered to your door every week.