What’s the meaning of Christmas? For many, it’s about feasting, family, and napping while watching the cricket.

But for e-commerce giants like Amazon, Christmas is the most lucrative time of the year. During the 2020 holiday season, Amazon processed more than A$6.6 billion in sales.

And for the warehouse and shipping workers who actually get these purchases to their destinations, the run-up to Christmas means long hours and more demanding work, often under poor conditions and with little job security.

In our research project on “automated precarity”, we are trying to learn more about workers’ experiences to understand whether conditions in Australian e-commerce warehouses are comparable to those documented overseas.

The Christmas rush

This year, almost four in five Australian households are expected to buy Christmas presents online.

The frenzy really kicks off with the manufactured “shopping holiday” of Black Friday, which follows the US Thanksgiving holiday but has become a global event. A single day wasn’t enough, so we now also have Cyber Monday, focused explicitly on consumer spending on e-commerce platforms.

E-commerce and Christmas have become so entwined that Dave Clark, a senior executive at Amazon, calls his company’s warehouses “Santa’s workshops”.

‘Tis the season of hiring and firing

We want to understand how things like seasonal shopping events and the promise of warehouse automation are shaping conditions for the growing number of logistics workers employed in e-commerce.

In Australia, Amazon has made extensive use of labour-hire temps engaged through recruitment agencies. Amazon Australia alone will mobilise more than 1,000 seasonal workers in the lead-up to the Christmas rush.

This temporary workforce often experiences some of the most intense working conditions. Aside from no job security, many workers are reportedly required to work at an accelerated pace for incredibly long hours, with the added expectation they will be available on call for the duration of the shopping season.

Burnout by design?

Traditional thinking in worker management suggests there are benefits to retaining workers who improve their skills and build loyalty to employers.

But in the United States, Amazon churns through workers at an alarming pace. Its annual employee turnover rate of 150%, nearly twice the industry average, has reportedly even led some executives to worry about “running out of workers”.

The urgency of seasonal shopping means Amazon can push workers to the max, making them work long hours doing physically demanding tasks at breakneck speeds.

Managers do not necessarily need to fire people when the rush ends – instead research and reporting suggests workers leave of their own volition, because their bodies simply cannot handle the strain any longer.

In a recent article, Canadian researcher and workers’ rights advocate Mostafa Henaway describes his experiences working in an Amazon fulfilment centre:

Amazon does not openly push people out the door. It lets the work do that on its own.

These conclusions are supported by reporting on working conditions at Amazon in different countries where the company operates, such as the UK and Italy.

Regardless of intent, burning through workers at a rapid rate is a consequence of how the work and conditions are designed.

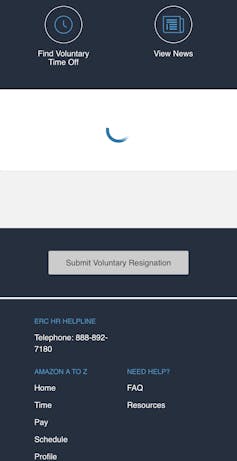

Amazon workers in the US report the app they use to manage their schedules even has a handy “submit voluntary resignation” button to make the process convenient and automated.

Internal documents reportedly show Amazon executives “closely track” and set goals for a metric called the “unregretted attrition rate”, which is the percentage of workers the company is happy to see leave every year. This applies to Amazon employees, rather than temporary labour, but could suggest churning through workers is an intentional management strategy.

As well as synchronising labour needs to seasonal demands, rapid turnover of workers makes organisation and unionisation less likely. In the context of an ongoing fight by Amazon workers to unionise, shorter-term workers are less likely to have the opportunity to become union members and push for better conditions.

We asked Amazon Australia whether “burnout by design” is a deliberate strategy. Director of Operations Craig Fuller said:

These claims are baseless. We’re proud to offer a safe, enjoyable and supportive work environment for our fulfilment centre team members all year round. As with all retailers, the holiday season is our busiest time of year, and we work hard to ensure that everyone working in our buildings is supported and has a positive experience at work.

This year we have onboarded around 1,000 additional seasonal workers around Australia to support our existing workforce over the festive season. While they are hired to work over the holidays, these seasonal opportunities can also present a path to employment and a longer-term career at Amazon and we have many examples of seasonal workers who have chosen to stay on and build their career with Amazon Australia.

We continue to place tremendous value and focus on the wellbeing and safety of our team.

Will automation fix it?

Online retailers are making big investments in automation.

Amazon is aiming to finish a new A$500 million warehouse in Western Sydney by Christmas. It will be the biggest in Australia, equipped with swarms of robots ferrying items around 200,000 square metres of floor space.

Increasing automation and reports of looming massive job losses can make workers feel threatened by the risk of being made obsolete by technology.

But this highly robotic workplace will still have plenty of human workers. There are plenty of things even the most advanced warehouse robots still aren’t good at, or that humans can do more cheaply.

Workplace automation is arguably less about replacing workers and more about pushing them to keep up with the pace of machines and algorithms. More speed takes its toll: Amazon warehouses in the US reportedly have an injury rate 80% higher than the industry standard.

The holidays are here to stay

We can expect corporations to further expand shopping holidays, following in the footsteps of Amazon’s mid-year revenue-boosting “Prime Day” in June. The exhausting and precarious conditions of seasonal work are likely to spread to the rest of the year.

We fear convenient online shopping comes at the expense of burnout, exhaustion, and precarious jobs. This situation may become permanent without improved labour rights and tighter corporate regulations.

Author: Christopher O’Neill, Research fellow, Monash University; Jake Goldenfein, Senior Lecturer, The University of Melbourne; Jathan Sadowski, Research Fellow, Emerging Technologies Research Lab and CoE for Automated Decision-Making and Society, Monash University; Lauren Kate Kelly, PhD Candidate, RMIT University, and Thao Phan, Research Fellow, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.