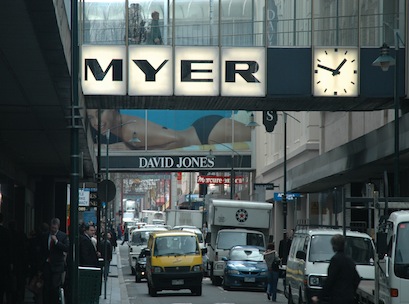

The world of retail is constantly bombarded with claims that data is what drives success. So explain to me how Myer – between Flybuys and the Myer One card database – sits on one of the world’s richest sources of big data, fails to compete with retailers that have – in some instances – none. David Jones is much the same. Hundreds of millions of dollars of shareholders funds spent over the last three decades on data collection, warehousing and reporting have produced nothing but declini

ng sales and shrinking margins.

Data can only record outcomes. It cannot tell you why. And data can be misleading. What retail data is progressively doing is dumbing the shopping experience down to commonality and – as technologists and financial modellers increasingly dominate the retail world – eradicating merchant flair and differentiation.

Far from being a ‘burning platform’ as some media analysts have suggested, department stores are becoming more not less relevant as a model, as customers struggle with the vast sea of me-too product options where the only life raft out of confusion is cheap price. It’s just that very few leadership teams in modern department stores around the world understand and can execute their proper place in the retail ecosystem.

Department stores used to be THE comparative shopping zone for customers. They should be the number one choice of customers to shop in any fashion or home lifestyle or gift related category. They should be, but very often they aren’t any more. That is because of what they have been allowed to become – little shopping centres rather than comparative and complimentary shopping zones that are a joy to shop.

Retailers like Myer and David Jones used to curate collections and present “this goes with that” stories to customer bases that floor staff knew by name. The store was not arranged in mini-stores (concessions) but rather set up so that customers could browse and select complimentary options in a category and have store staff take them through what would be best for them and why, at the same time as adding more items to the basket by embellishing the initial item to deliver a better outcome for the customer.

Width of range and depth of service is what drove customers into stores because width meant all options and all categories of need in one place and service meant best personal outcome. Yes – on paper – capital efficiency could be improved by tightening ranges. But it killed customer connection and drove department stores into competition with other retailers who could match them on tighter ranges and beat them on price.

Efficiency is not the sole driver of retail success. Today we have department stores driven by concessions, with no connection between branded range options and very little service in stores that aren’t built for self-service. Historical strength categories have been removed entirely. Yet some are suggesting we combine two poorly performing retailers together as a solution as if ‘synergies’ will solve it.

Our department stores cannot only be saved, in time they can flourish. But ‘can’ and ‘will’ are two very different things and it will take blood, sweat and tears to get them back to where they should be. Something investors are becoming less and less willing to tolerate.

Peter James Ryan is a retail expert and head of Red Communication. 02 9481 7215 or peter@redcommunication.com.